1989. There are several ways to go about your discovery of PKD. You can read his best novels; you can read his best stories; you can scrounge around garage sales and on-line for old magazines with his earliest works; you can read essays and interviews by and about him in those old mags, and increasingly in the “mainstream” periodicals as his work caught on and the “mainstream” caught up; you can rent the movies made from his novels and stories then you can read the underlying works and compare them to the Hollyversions; and if you really want to go deep, you can read Exegesis, PKD’s eight-year, eight-thousand page hand-written quest to answer his two BIG QUESTIONS: WHY ARE WE HERE? and WHAT IS REAL?

Or you can read Lawrence Sutin’s excellent biography. Written within seven years of PKD’s death, this bio is smart, thorough, and close to the subject. Sutin read it all – over forty novels and two hundred stories, the then unpublished Exegesis, and a lifetime’s correspendence – no small feat. He interviewed Phil’s surviving family and friends and fellow writers. Through it all, he exhibits honest respect for his subject, hairy warts and all.

NOTE: I just found this comment on Amazon from Tessa Dick and add it for perspective:

I have mixed feelings about this book. Sutin gives the impression that he interviewed me extensively, but he actually used quotes from other interviews and never met me, although I did briefly answer three of his questions by letter. Furthermore, I must disagree with most of his conclusions. Since I spent ten years with Phil, and those were the last ten years of his life, I believe that I know more about him than a biographer who never met him and simply read about him.”

Wherever you start, PKD is a literary journey worth taking.

Then there is PKD the man: an only son whose twin sister died at one month and who by his own admission spent the rest of his life looking for her replacement. PKD married five times, fathered a son and two daughters, fought money troubles most of his life, attempted suicide at least once, and abused pharmaceuticals to sustain his energy and alleviate his phobias and anxieties. He loved cats, loved his children, fell in love at the drop of a hat – especially with dark-haired girls half his age – and was often generous with his friends and family.

Coming of age in the SciFi boom of the 50’s when success accrued to the writer who could crank it out the fastest, PKD learned to write – and type – at break-neck speed, at one stretch composing on average fifty pages a day for weeks at a time. As he aged, the drugs which helpd him sustain that pace took their toll, and he learned as did everyone who enjoyed the synthetic highs of the 60’s, that drugs had their dark side. He called Through a Scanner Darkly his anti-drug statement, even writing to the FBI to volunteer as a spokesman for anti-drug PR efforts.

As successful as PKD was at SciFi, his first and abiding ambition was to break into “mainstream” literary fiction. His only such breakthrough during his life was Confessions of a Crap Artist, published in 1975 to modest success. My intro to PKD happened to be that book which I found in a dime store on a rotating book rack. I was a lit major and had suckled on serious stuff, ya’know, but I often supplemented my diet and fattened up on richer fare. Crap was rich, and I was blown away by its energy, its humor, and its honesty. Who knew reading could be that much fun? It’s like it wasn’t even work; the words flew off the page and the pages turned themselves. Who was that guy?

I’ve since read some of his better books, some of his better stories, and plowed through all of Exegesis. None of it has disappointed. Of course, I’m a fan. And at this stage anything with his initials is going to interest me.

PKD was a man of ideas rather than a man of action. He wrote himself into physical and emotional hell, or he wrote himself out of physical and emotional hell. You could look at it either way. However you choose, he left us with a body of work that is as unique and powerful as anything from the second half of the twentieth century.

After a visionary experience in Feb/March 1974, PKD spent the last eight-and-a-half years of his life writing to try to understand the two BIG QUESTIONS. Exegesis is interesting because of PKD’s fiction. Exegesis is an exploration that doesn’t arrive at any conclusions. It asks THE QUESTIONS and discards every answer to further test corollaries and opposites and take unexplored paths. He read deeply and widely, dreamed constantly, thought and argued with himself consistently, and talked for hours to friends who would listen. Who knows, he may have understood THE BIG QUESTIONS a little better at the end, and as only he knows, he may have been ready for death when it came.

PKD left us with a body of work that is entertaining, provocative, funny, and capable of skewing your view of reality just enough to perhaps help you perceive it a bit more clearly. If that’s not mainstream fiction, PKD, I don’t know what is.

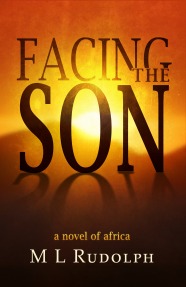

Undocumented workers, barrio punks with guns, high-tech strip clubs, grubby city politics, and a backpack full of dirty money—all play a part in the smart new crime novel, Pasadena Payback, by my friend and fellow indie author, M.L. Rudolph. The action mostly takes place in Pasadena, best known for its Rose Bowl and festive parades, but it starts with a gripping scene on the Arizona border and inevitably leads back there for its life-or-death finale. Serious stuff, but it’s getting there that makes this a fun, fast-paced book.

Undocumented workers, barrio punks with guns, high-tech strip clubs, grubby city politics, and a backpack full of dirty money—all play a part in the smart new crime novel, Pasadena Payback, by my friend and fellow indie author, M.L. Rudolph. The action mostly takes place in Pasadena, best known for its Rose Bowl and festive parades, but it starts with a gripping scene on the Arizona border and inevitably leads back there for its life-or-death finale. Serious stuff, but it’s getting there that makes this a fun, fast-paced book.